The day is still dawning, hazy and gray from Gravana, when, pointing to the southwest and the heart of the island, we notice a strange coexistence of names, some familiar, others, above all, strange and that wouldn't even remember the devil.

Almeirim appears in the vicinity of Blublu. Água Creola overlaps Caixão Grande.

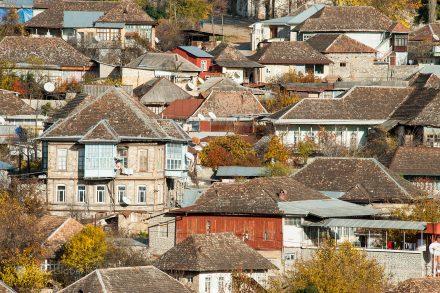

António Vaz precedes Trindade, capital of the Santomean district of Mé-Zochi and second city of São Tomé, even if it is only seven kilometers away from homonymous capital.

In Trindade, the old CTT building with its round facade is still closed. In front, a few officials advance on their way to their posts.

And groups of residents, pointing to a source of drinking water painted green, matching the wood business next door.

Trindade is home to more than six thousand inhabitants, only a tenth of the population of the capital.

From time to time, one of them is the President of the Republic of São Tomé and Principe, housed in a pink mansion set on a verdant hill, shaded by palm trees with large crowns.

This inaccessible mansion intrigues us for a moment. The yellow colonial building, with its high doors and windows and attic openings on a roof that has been oxidized by the years, stands out from the humid gloom of the landscape.

It compels us to photograph it in different scenes, with passers-by and the traffic that circulates there.

The Colonial Taint of the Batepá Massacre

Alongside Batepá, Trindade was one of the poles where the colonial violence inflicted on the black population of Santomean proliferated and which many believe to have triggered their nationalist sentiment and independence yearning.

It was generated by the Governor-General made Calígula of the archipelago, Carlos Gorgulho.

Appointed in 1945, artillery colonel Gorgulho dictated a series of laws and measures aimed at controlling the community of farm servants and the like.

They aimed, in particular, to prohibit forms of subsistence to which the natives were beginning to get used to, such as the sale of palm wine and sugarcane brandy, drinks that Gorgulho considered that reduced the productivity of workers.

As if that were not enough, he increased the labor tax.

The development that Carlos Gorgulho wanted to ensure with slave labor

At the turn of the 50s, Gorgulho also put into practice an ambitious plan for the urbanization of the islands of São Tomé and Príncipe.

It combined a new residential neighborhood for employees, arranged in the middle of Av. Marginal, a municipal market, new airports, a stadium, a cinema and a network of avenues and streets that connected the planned buildings.

So far so good. The enslaving abuse would have been repeated, however, when recruiting workers for the said works.

It is said that Gorgulho tried to resolve it by publicizing that the State was looking for wage earners for various posts. When candidates came forward, they were informed of an unexpected lack of funds to remunerate them.

Shortly afterwards, they found themselves surrounded by the police and forced to work for the equivalent of one Euro a day, much less in the case of volunteers. In Trindade, specifically, only five or six candidates appeared for about thirty vacancies.

Frustrated, Gorgulho orders the police to sweep the island looking for undocumented workers to force the labor brigades to fill up. The police do it with such zeal that those targeted create alarm procedures against work based on kidnapping and manipulation based on whipping and other corporal punishment.

Accordingly, the lack of manpower for Gorgulho's projects remained unresolved and was made worse by the impossibility of recruiting workers in Angola, a colony that suffered from the same problem. Other rumors arose that made the Linings (so the potential victims were called) feel cornered.

The conflict intensified. In Caixão Grande, an Angolan policeman is the victim of a machete blow. Days later, anonymous writings appear on the walls of Trindade threatening Gorgulho with death if he continued to try to bend the Forros (farm workers).

On the same day, Anonymous Forros take notices of jobs placed by the authorities. The authorities announce that they will pay the equivalent of five thousand euros to those who report the offenders. From then on, the lack of manpower became even more complicated.

Like the mutual distrust and aggressiveness that did not take long to fall apart.

Carlos Gorgulho's Paranoia and the Dissemination of Violence

The paranoia that the Santomeans were preparing an uprising worsened in Governor Gorgulho's mind. Gorgulho reacted in a preventive and extemporaneous manner.

It mobilized the Portuguese colonists to arm and protect themselves. The plantation owners recruited Cape Verdean, Angolan and Mozambican workers.

On February 3, Gorgulho instructed the CPI (Indigenous Police Corps) and other authorities, with the help of landowners, to capture, beat, torture and murder hundreds of suspects, mainly from Trindade, Batepá and surrounding areas.

In certain cases, the massacre took place in terrible ways.

In the aftermath of the killing, Gorgulho would have uttered “throw all this shit overboard, to avoid problems”. His employees followed the order to the letter.

Marco de Batepá and the Shame that Subsists

From Trindade, we head to Batepá. There we find a landmark painted in different colors that remembers the tragedy and its victims. Paintings around the memorial recreate its most gruesome details, such as a truck dumping corpses into the Atlantic.

We came across a group of visiting friends. One of them, who wears a shirt of the Portuguese national team, asks us to photograph him next to the memorial. The companions turn up their noses, bothered by the request.

They beg you not to. Confident in his principles of Portuguese brotherhood, the boy replied “Stop it! Santomean people are ignorant!” said just like that, as the Santomeans do, with the r loaded.

From Roça de Santa Clara to Roça de Bombaim

We pass through the Santa Clara farm. In its plantations and sanzalas, we see a misery of the workers comparable to what the antecedents suffered in the times of Governor Gorgulho.

To which is added the unavoidable data from Cape Verde and the times of poverty and hardship, at least free, in the islands of the Macaronesian archipelago.

Wilson, the guide who guides us, takes us along a path that cuts through the rainforest, which serves as a shortcut to a swidden to the south, in times concurrent with Bombay.

We find Bombay – the village and the farm that gave rise to it – on the edge of the vast wild and untamed domain of the Ôbo Natural Park.

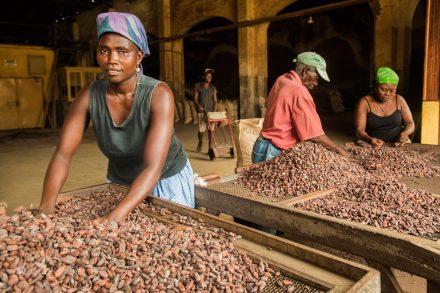

Bombay emerged as another of the many coffee and cocoa producing plantations on the island. It had its peak of production and profit.

Roça Bombaim and the Decline that Lasts

With the abolition of slavery and the internationalization of cocoa production, entered the process of decay in which we find it. Several buildings are ruined, given over to fig trees and other bushes. As always happens in São Tomé,

The bare and degraded sanzalas are still home to some Santomeans. Less and less in Bombay.

In 2001, the place welcomed 30 souls. A decade later, there were less than twenty.

A kid walks along the rutted path in the grass, towards us. Shy, he gains courage and introduces himself. It's Lucas. We follow him among ducks, chickens and pigs, to the section of the sanzala occupied by his parents.

We salute you. Immediately, we felt them absorbed. As if sedated by the abandonment to which they were voted. An inscription made in charcoal on a wall sums up their condition: “Roça Bombaim. Damned city. Fulfill yourself”.

Even though everything remains to be done, just before we leave what's left of the field, Lucas' father stops us by the car. He offers us a bouquet of porcelain roses that he had just composed.

We say goodbye moved. With a mixed feeling of guilt and powerlessness for leaving them like this. And yet, this is what almost all visitors to Bombay and the plantations do.

The New Life of Roça Monte Café

Unlike Mumbai, the Monte Café swidden we passed next, at an altitude of 670 meters, is home to an abundant population.

It insists on an attempt to recover the production of Arabica coffee and cocoa which, inaugurated in 1858, makes it one of the oldest in São Tomé.

From that date until its decline, Monte Café generated enough profit to expand and build its own hospital.

When we walked through it, we found young families living in part of the premises.

Another section is managed by Taiwanese who, as part of their support program for São Tomé and Príncipe, provided appointments twice a week.

Mist hangs over the forest above the swidden.

From time to time, it settles down and cools down the kids who play up and down the old staircases and pathways that join the secular buildings.

Gradually, the freshly picked coffee dries up. we lack the time São Tomé and their swiddens were lost.