A peak reveals the vastness of an anhara set in a gentle valley.

Road 140 intersects it, going up and down, lined with yellowish grasses that recent rains have caused to grow well above a tall, broad-shouldered Angolan man.

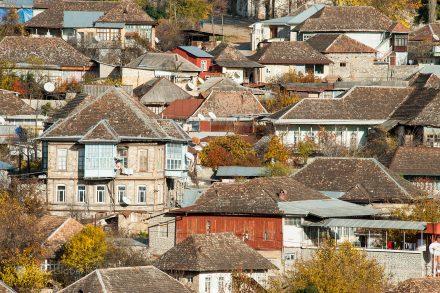

We stop to admire the landscape and the village of adobe and thatch that stretches out on the opposite top, on both sides of the asphalt, under a caravan of white clouds.

As we do so, a figure approaches and defines itself.

A boy in a football t-shirt, flip-flops and headphones in his ears was going up the slope humming unceremoniously.

“This song is good!” we shoot, by way of salute.

“It's not bad, father and mother” he replies with a courtesy that exposes the importance of age and family structure in the still quasi-tribal society of this interior of the province of Malange.

We proceed. We crossed the village.

We pass beyond the ridge and, not long after, through a square called the Deviation of Terra Nova.

There is a vegetable and fruit market where dozens of locals sell and suggest their products.

A little anxious to complete the journey, we thank them for the offers, but we continue, the last kilometers, along a tertiary road, narrow to match, almost swallowed by the savannah, where large faults and holes force us to zigzag without appeal.

Other villages of adobe and thatch follow. The village of Meio marks the core of the new roadside housing line.

A field bridge allows us to cross the Cole, a tributary of the Lucala, the river we were looking for.

We passed women with firewood, or bowls, at their heads, which the narrowness of the road forced them to collect into the vegetation.

Soon, for a last settlement. A climb leaves us facing a gate.

Entrance to Pousada Calandula

The guard salutes us and lets us through. Moments later, we parked at Pousada Calandula, next to logs, stumps and chips destined for firewood.

Receive us Samuel.

The young host of service and delicate manners confirms what we expected. On a Wednesday, we are the only guests at the inn.

When we settled in, we opened the door to the balcony. The roar of the homonymous waterfalls is then amplified.

We can see them in their absolute premiere, from the top of their 410 meters long and 105 meters high, a colossus of river collapse that leaves us enthralled.

In Africa, only victoria falls surpass those of Kalandula in grandeur. In the rest of World, of the Iguazu-Iguazu.

While Samuel was lighting the fire for the night, we were already going out to discover.

As he explained to us, two trails that were almost opposite made it possible to reach the top and bottom of the falls.

Kalandula: from the First Vision to the Top of the Waterfalls

We take the one at the top, along a slope between crops and dense forest. The path leaves us on the high left bank.

Over there, a few kids bathe in natural pools bordered by rocks. Two or three adults fish in a river border branch.

One of them offers himself as a guide. We thank you, but remember that it was almost dusk. The next day I couldn't. Even so, it clarifies something that, only in part, we would prove.

By road, the other side of the falls was almost an hour away.

During the drier season, those who knew the river well could cross to the other side, on foot, at its top.

Half an hour after sunset, we return to the inn. We dined like princes, with a view of the fireplace and the comforting aroma of wood.

We are lulled by the roar of the falls, accompanied by the croaking of the resident frogs.

Samuel had already warned us: after waking up, when we open the windows to re-appreciate the falls with the sun just rising, we almost don't see them.

Mist generated by the concentration of humidity around the river basin, enveloped them in an erratic whiteness, more or less dense, depending on the whim of the breeze and the emerging vortex of sprinkling.

It was the same humidity that kept the surrounding savanna still green, that kept the immediate jungle stronghold lush.

Kalandula: the Long Journey to the Other Side of the Falls

We get tired of waiting for the sun. We get in the car. We pointed to the viewpoint on the other side of the river, determined to stop whenever the path justified it.

The holes in the road made us pass through the villages at a contemplative pace.

In each of them, upon hearing the approach of the car, crowds of children rush to the asphalt: “Friend, cookies!!” they shouted almost in chorus, some with a demanding tone, determined to receive the tasty gifts to which previous outsiders had accustomed them.

The adobe harmony of the villages and, in particular, a stronghold full of dozing goats, justifies an immediate stopover. In three times, the residents of Aldeia do Meio surround them and the car.

As we wander among the houses, women and girls in traditional costumes pose for us with a charm and ease that delights us.

After almost an hour of socializing, when we returned to the car, we noticed that dozens of children were surrounding and staring at it.

When we asked them what they were doing, an old man was quick to explain: “they are amazed at the shadow.

These little ones are not used to seeing her.” By “shadow” he meant the reflection on the plate.

We gave the cookies and other gifts that the community was counting on to some of the mothers closest to us. Then, we proceeded to the viewpoint.

When we got there, the sun had already dissipated the morning mist.

From the panoramic supremacy that sheltered us on the precipice gave us, we admired the waterfalls, the sparkling rainbow over the beginning of the Lucala River.

And the wild flow, with its verdant banks, that zigzags through the savannah, in the path of its older brother, the Kwanza River.

In the car park at the falls, a few guides welcome us.

Polite and courteous, Marcos Dala accompanies us and informs us about everything.

He even convinces us to go down to the base of the falls, from where, he assures us, the perspective and proximity of the rainbow would amaze us twice as much.

From Top to Bottom of Kalandula Falls

We followed him and a colleague down the ramp, talking about everything, including the colonial past, the civil war and the complex political and social evolution of Angola.

On the banks of the Lucala, we come across a fisherman stuck in the water, spreading a net in the imminence of the furious rapids.

Marcos' colleague buys him some fish, as a reward for that unusual risk of his life.

Moments later, over a muddy trail, we are facing the falls.

The direction of the breeze caught us with a soggy view, with no sign of the rainbow, which made us anticipate the return to the viewpoint.

With the kwanzas we paid them, Marcos and his colleague had won the day. They could go home.

We give them a ride to the town of Kalandula where they used to live.

Incursion to Kalandula Povoação

We take the opportunity to take a peek at the village, in the image of the falls, known until Angolan independence in 1975, as the Duke of Bragança, an old baptism in honor of King D. Pedro V who simultaneously held this other noble title.

In Kalandula city, murals on buildings exacerbated Angolan nationality.

And, right next to the local MPLA headquarters, portraits painted on a long cream wall, the main figures of the party: Agostinho Neto, José Eduardo dos Santos and the current president João Lourenço.

Some murals decorated ruins of colonial houses. Its coloring conceals the historical reality.

Shortly after independence, for a long time, this entire area was controlled by UNITA.

It is disputed by the rival party in battles so destructive that they left the region and much of the province of Malange in pieces, a good part of its population forced to take refuge in the confines of Angola and even abroad.

The Return of the Old Pousada Calandula

The Pousada Calandula, built in 1950, in the middle of the colonial era, was also abandoned for a long time, only reopening in 2017, thanks to the investment of businessman Francisco Faísca.

We even spent a second night there. A kind of confirmation of the wonder in which the falls kept us.

And as a providential extension of the work we dedicated to them.