From Pemba to Ibo: an Epic of Plate and Boat

The Quirimbas and its Ibo island, in particular, are another of those places that we fear are difficult to reach but which, in a shorter time, we end up reaching without any hitches. After persistent investigation, we had found that the “chapas” were leaving Pemba around four in the morning.

We managed to convince Chaga, one of the drivers, to pick us up at 3:30 am. In spite of the suffered awakening, at this hour we had our bags packed at the entrance to the hotel. Chaga lived up to the name. At the agreed time, he was still struggling with the sheets. He only managed to fill the “chapa” and leave Pemba around 5am.

We let the tours around the city lull us and slept as much as we could. After four and a half hours along sandy roads flanked by cornfields and parched cassavas sprinkled with baobab trees, we bumped into the terrestrial threshold of the village of Tandanhangue.

There, several vessels waited for the tide to rise and make the mangrove channels onward navigable. At around eleven, a dhow set sail to the pine cone of natives and their cargoes, decked out in the many capulanas, shirts, hijabs and headscarves of the women on board.

A dhow owner renews the paint on his boat.

It took two hours longer than a small reciprocating boat. So we got into the latter and shared the last water route with ten other passengers, including residents and visitors of Ibo.

We disembarked at one o'clock in the afternoon, and went to the Miti Miwiri hotel, as the name in the Kimuani dialect translated, located between two large trees, in the heart of Praça dos Trabalhadores, in front of the coal sack deposit that served the island.

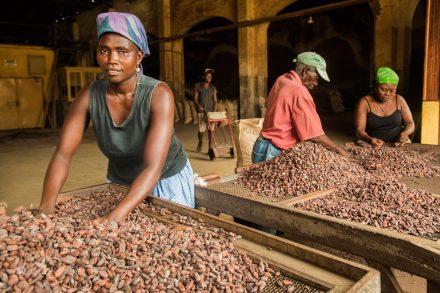

Seller among sacks of charcoal on Rua da República.

The First Deambulations by Ibo

The hotel was rebuilt from the ruins by two young friends, a German and a Frenchman. Jörg, the German, had fallen in love with Ibo and Mãezinha, once a mere maid, now the owner's partner and right-hand man. The early morning awakening and the long journey took all of our energy.

Shortly after check in, we gave in to fatigue. We only woke up in the following morning, looking forward to a good breakfast and to inaugurate the discovery of the island.

Its São João Baptista fort, in particular, named in honor of the island's patron saint and representative of the Portuguese colonial past in Mozambique, seduced us.

We found it occupied by an army of artisans. Those dedicated to silver jewelry and precious and semi-precious stones are installed in the wing adjacent to the entrance gate. Others, those gifted in the Maconde art of sculpture of black wood and other types of wood, worked withdrawn in interior rooms. We scrutinize your work thoroughly. Then we ascend to the upper level.

Children lie on the bed soaked by the rising tide, in front of the Fort of São João Baptista.

Large white clouds parade across the blue sky in the dry season. It is under its intermittent shadow that we walk along the boulevards adapted to the polygonal shape of the fortress, erected in a position that allowed the targeting of enemy vessels, forced to circumvent the northern outline of the island to approach its main settlement.

The tide is empty once more. To the north, newly disembarked figures crossed the bog that preceded the collected flow of the Canal de Mozambique, farther north of the island Bazaruto that we had explored a few days earlier. We skirted the fort with the idea of getting closer.

When we do this, a line of women with bales on their heads emerges from among the colony of cacti that surrounds the monument and settles in a dhow waiting to rise from the sea.

Rise and the Sudden Disappearance of the History of Mozambique

Until then, that was the pattern of local life that stood out the most. From 1609 onwards, Ibo had its era of prominence, events and commotions. From 1902, with the passage of the capital of the Mozambican province of Cabo Delgado to Porto Amélia (today, Pemba), the island was left to the flow of time and tides.

From the Indian Ocean, there was little more than the beach-sea, fishermen and the occasional stranger, like us, attracted by its enigmatic retreat.

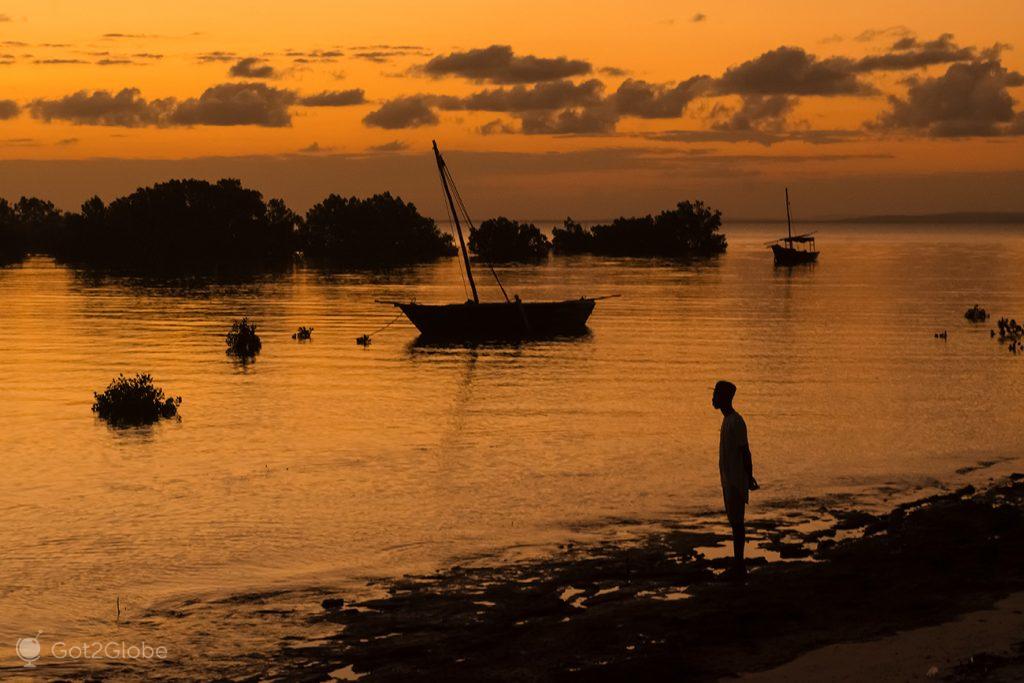

Dhow approaches the pier of the village of Ibo, with the sun almost sinking behind the horizon.

The fort was erected in 1791, almost 300 years after the time when Vasco da Gama is said to have landed and rested on the island, 270 years since it replaced the São José do Ibo Fort, its first fortification. At the height of the eighteenth century, Ibo was at its economic apogee, achieved thanks to the fruitful slave trade.

The village had just been promoted to a town and, soon, the capital of the province of Cabo Delgado. With the resident government assisted by a City Council and a court, the strengthening of the island's defense became urgent. In addition to that of São João, half a century later, that of Santo António do Ibo would be built.

From the fort of São João Baptista, we retreat to the main pier of the village, located at the entrance to the inlet, next to the fort of São José and the coral and limestone church of Nª Senhora do Rosário.

The church of Nª Senhora do Rosário, between two of the forts that once defended Ibo island from incursions

Ibo and the Quirimbas. A Life at the Taste of the Tides

More than a pier, the raised jetty, sometimes over the sea, sometimes over the mud, serves as a resting and social point for a clientele of residents who meet there and share the rare news of the day.

With the tide at its height, groups of children gather there, armed with a line and hook, and spend their time in an always useful recreational fishing.

Guys fish by line from the tip of the pier that serves Ibo

We return to the heart of the city, meanwhile with the company of Isufo, a young native who we ended up taking in as a guide. Together, we passed between the church and the small statue in honor of Samora Machel.

When we walked along Rua da República, between the colonnaded porches of the old houses, some restored, others decrepit and even in ruins, we noticed that, to the left, a Rua Almirante Reis branched off from it. We return to Miti Miwiri and cut to Rua Maria Pia. Ibo's historical familiarity never ceased to grow.

Mr. John the Baptist, the Resisting Elder of the Colonial Period

On this road, which is also covered by a porch, we come across the house of Sr. João Baptista, former 3rd official of the colonial administration. At the time of our visit, at the age of 90 and retired for many years, Sr. João takes on the role of adviser and historian of the island.

Until some time ago, a round sign hanging from his porch identified him as such. As soon as we found him, the physical form, the joviality of his face and, in particular, the laughter and other expressions, slightly childish and cunning, surprise us.

Mr. João Baptista, in this image, aged 90, retired from many years in the service of the Portuguese State.

However, sheltered from the sun, João Baptista describes to us a good part of his life. “Well, I was the first black person to be able to attend the local primary school, among white people.

Later, with the necessary education, I entered the service of the state. I worked in Beira and elsewhere. After many years away from my homeland, I managed to get transferred here. During the war of independence, Ibo was so far from the mainland and the stages of war that everything remained calm.

I only got a fright when an independence activist, out of sheer malice, accused me of being a collaborationist and arrested me. But then, as they had nothing to point out to me, they let me go and left me alone.”

João Baptista liked both his story and Ibo's, which, after all, intertwined with obvious frequency. It is with pleasure that he summarizes for us how the civilization we find in it developed. “At the origin, the native blacks and blacks of these parts inhabited the island and other Quirimbas.

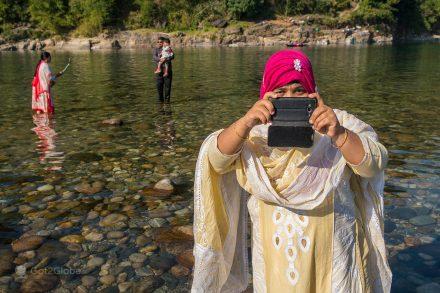

Ibo woman in the traditional hijab long worn in these parts of northern Mozambique.

The Arabs were the first outsiders to arrive in these northern parts of Mozambique. Here they founded a fortified trading post. From here they dispatched gold, ivory and slaves to Zanzibar and other destinations in the Arab world.

When the Portuguese arrived, they found an island that, contrary to what they were used to, had several well-distributed wells. They called it Well Organized Island. From this qualification, the term IBO emerged.

They also find indigenous black population, some Swahili and Arab. Arabs centered on Quirimba island they refused to trade with them. Furious, the Portuguese set fire to their village, sank a good part of their dhow, killed dozens of rivals and seized their goods.

Thereafter, Ibo and other Quirimbas were used as a stopover for their ivory and slave transactions. Until the frequent attacks by corsairs and Dutch forces and coming from Madagascar forced them to fortify themselves as never before. Ibo was one of the last places in Africa to comply with the British imposition of an end to the slave trade.”

We continued to talk until we noticed that the event was on the horizon. We interrupted the meeting with the promise that we would return.

Senhor João took his leave with the same cordiality with which he had received us. We watch the sun sink into the amphibious mangrove forest that encompassed much of the island. Ç

With the dark installed, we collected the Miti Miwiri.

I figure by the sea during sunset over the Mozambique Channel.

New day, the Same Ibo Lost in Time

At 8 am the next morning, Isufo was already waiting for us at the door, willing to show us the heart of Ibo and some of the less exposed corners of its 10 by 5 km.

We peeked at the old cemetery. In it we find an unexpected assortment of graves of Portuguese, Iboans and other Mozambicans but also of British and Chinese.

We go through interior paths, dotted with coconut trees and baobab trees.

We cross villages that group together huts or mud huts, where the women with golden mosseiros pound the manioc and corn and the maçanicas dry in the sun.

We return to the surroundings of the São João Baptista fort. The tide was already rising up a coral slab on a section of shore where fishermen anchored their dhows and sold their afternoon catch to a colorful and excited crowd. We walked this way and that, on the sharp marine stone, watching the turmoil unfold.

We admire the fishermen's duties and the buyers' anxiety, who find it strange but tolerate our boring photographic action.

We also accompany the efforts of the robust men who carry dhow bigger than all the others with sacks, barrels, motorcycles and even refrigerators.

Fishermen anchor along the coral coast, awaited by a small crowd of buyers of their fish.

We asked one of the buyers of the fish, meanwhile exposed in a tarpaulin, where they are going to sail with such a load. "Soon, go south of the Tanzania, answer us. There is some movement of people to and fro.”

Apart from the arrival and departure of visitors and the improvements carried out to better receive and impress them, it was one of the few symptoms of the end of the long stagnation to which Ibo Island was doomed that we were able to observe.

More information about Ibo Island and the Quirimbas on the respective page of UNESCO.